what one imagines

lost souls look like

|

Finding themselves

transported to some other world

(Die Ausgewanderten)

(Die Ringe des Saturn)

|

"Es war ein Fluchtweg, etwas ganz Privates", murmelt Max Sebald, während er in einem dicken Ordner mit alten Fotos wühlt. Ein Junge in weißem Kittel und Kaftan, ein Friedhof mit schiefen Grabsteinen, ein Kurort zur Jahrhundertwende: Es sind Fotos, wie man sie in einem Trödelladen findet, wenn man in einer Postkartenkiste blättert. Und dort hat Sebald sie mehr oder weniger gefunden. Er habe schon jahrelang Fotos gesammelt, bevor er mit dem Schreiben begann, erklärt er, und die Läden in den Küstenstädten von East Anglia, wo er seit seiner Emigration aus Deutschland im Jahr 1970 lebt, nach Bildern durchforstet, die er in seine Bücher einbauen konnte - oder besser gesagt, die als Katalysator für sie dienten. "Nicht einmal die Leute im Haus wussten, was ich vorhatte; ich zog mich einfach in meine Werkstatt zurück und töpferte herum. Ich glaube, es waren diese Fotografien, die mich schließlich dazu brachten, mich zu überwinden.

|

|

Sie hatten auch mich überwältigt. Tatsächlich waren sie ein wesentlicher Grund dafür, dass ich bei einem Kaffee in Sebalds gemütlichem, mit Büchern ausgestatteten Arbeitszimmer in Norwich saß. Ich war auf einer literarischen Pilgerreise gekommen." The Emigrants", sein englisches Debüt, das vor drei Jahren in einer eleganten Übersetzung von Michael Hulse erschienen war, war wie kein anderes Buch, das ich je gelesen hatte. Zwischen dem Text - einer Abfolge biografischer Erzählungen über Deutsche, die durch den Holocaust ins Exil getrieben wurden - waren Fotos ohne Bildunterschriften eingefügt, die aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen keinen Sinn ergaben. Warum ein Rasentennisplatz mit blattlosen Winterbäumen im Hintergrund?

| |

Warum ein jüdischer Friedhof, der von Weinreben überwuchert ist?

| |

Warum die Turmspitze des Chrysler Buildings und die Brooklyn Bridge?

| |

|

Sein neues Buch, Die Ringe des Saturn, angeblich eine Zusammenstellung zufälliger Notizen, die der Autor während seines Aufenthalts in einer psychiatrischen Klinik begonnen hat, ist eine Fortsetzung dieser eigentümlichen Mischform. Der schwer fassbare Erzähler, ein akribischer Amateurhistoriker von East Anglia, wandert mit einem Rucksack auf dem Rücken durch die Landschaft und erzählt in der abschweifenden, aber hypnotischen Prosa, die Sebalds Markenzeichen ist, von den Überlieferungen, die er über die mittelalterliche Vergangenheit der Gegend, die längst verstorbenen Bewohner der verfallenen Herrenhäuser und die Archäologie der malerischen Küstendörfer gesammelt hat. Wie Die Ausgewanderten ist auch Die Ringe des Saturn mit geheimnisvollen Fotografien illustriert, die den ebenso geheimnisvollen Text untermalen und verdeutlichen.

Und wie sein Vorgänger wird es in der Stimme eines namenlosen Ichs erzählt, dessen Identität unbestimmt ist. Sein seltsamer Monolog über die Verwüstungen der Geschichte wird durch Passagen aus den Werken von Swinburne, Chateaubriand, Borges ("Ich fragte Bioy Casares nach der Quelle dieser denkwürdigen Bemerkung, der Autor schreibt . .") und Joseph Conrad, der einst an der Nordseeküste segelte, als er noch der Seemann Jozef Korzeniowski war. Nach einer detaillierten Zusammenfassung von Conrads frühem Leben geht Sebald auf die traumatische Reise des Schriftstellers in die tiefsten Abgründe des belgischen Kongo ein, die ihn zu seinem Meisterwerk Heart of Darkness inspirieren -

dann kehrt er abrupt zu einem Bericht über seine eigenen Reisen zurück, wobei der Fortgang der Erzählung durch Assoziationen an Belgien unterbrochen wird:

Auf jeden Fall entsinn ich mich genau, dass mir bei meinem ersten Besuch in Brüssel im Dezember 1964 mehr Bucklige und Irre über den Weg gelaufen sind als sonst in einem ganzen Jahr. Ja, eines Abends habe ich in einer Bar in Rhode St. Genèse sogar einem verwachsenen, von spastischen Verrenkungen geschüttelten Billardspieler zugesehen, der sich, wenn die Reihe an ihm war für ein paar Augenblicke in einen Zustand vollkommener Ruhe versetzen und dann mit unfehlbarer Präzision die schwierigsten Karambolagen bewältigen konnte. Das Hotel am Bois de la Cambre, in dem ich damals für einige Tage wohnte...

Und so geht es weiter, von einer zügigen Bestandsaufnahme der schwerfälligen Möbel des Hotels zu einer Betrachtung des hässlichen Denkmals, das die Belgier zum Gedenken an die Schlacht von Waterloo errichtet haben. Für Sebald sind die Diskontinuitäten des Unbewussten die Hauptstütze seiner Kunst.

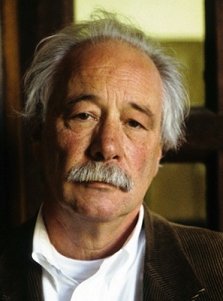

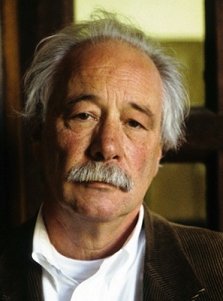

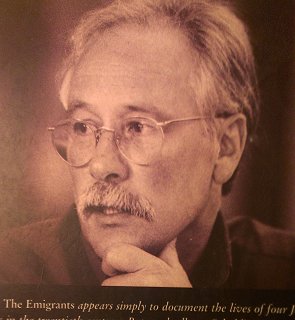

Sebald, der vierundfünfzig Jahre alt ist, spricht mit einem ausgeprägten deutschen Akzent, aber sein Englisch ist auch nach fast drei Jahrzehnten noch anspruchsvoll und präzise. (Wie viele englische Muttersprachler wissen, wie man das Wort apodiktisch in einem beiläufig hingeworfenen Satz verwendet?) Mit seiner schütteren Mähne aus weißem Haar, der randlosen Brille und dem buschigen Schnurrbart ähnelt er dem Frankfurter Theoretiker Walter Benjamin. An diesem Spätwintertag trägt er eine unauffällige Kordhose und einen dicken Pullover; nur der Schnurrbart und die Zigarette, die er in einer Halterung raucht, lassen auf seine kontinentale Herkunft schließen. Er stellt sich mit seinem Spitznamen vor - Max.

Sebalds Bücher entziehen sich einer einfachen Klassifizierung. Sind sie Fiktion oder Sachbuch? Geschichte oder eine Borges'sche Erfindung, die auf Tatsachen beruht? Sein Verleger hat sich vorsichtshalber für die Doppelkategorie Belletristik/Literatur entschieden. "Es ist schwierig für die Verleger", räumt er ein. "Sie müssen sicherstellen, dass es nicht in die Reisesektion kommt. Als ich versuche, ihn darauf anzusprechen, weicht er geschickt aus. "Fakten sind problematisch. Die Idee ist, es so aussehen zu lassen, als ob es sich um Tatsachen handelt, auch wenn manches davon erfunden sein könnte." Wahrheit, wie sie ein Historiker oder Biograf versteht, ist für ihn letztlich irrelevant. "Ich möchte einfach nur anständige Prosa schreiben. Was auch immer es ist - biografisch, autobiografisch, topografisch -, es spielt keine Rolle. Ich habe eine Abneigung gegen den Standardroman: `Sie sagte, und ging durch den Raum'- das hat etwas Banales an sich. Man spürt, wie sich die Räder drehen."

Sebalds Bücher sind konsequent handlungslos. Ihre erzählerische Linie folgt den Konturen des Unbewussten. Seine Methode besteht darin, eine Collage aus scheinbar zufälligen Details zusammenzustellen - verstreute Bruchstücke der persönlichen Geschichte, historische Ereignisse, Anekdoten, Passagen aus anderen Büchern - und sie zu einer Geschichte zu verschmelzen; Sebald nennt das, in Anlehnung an Claude Levi-Strauss, Bricolage. Der Effekt ist eine Art organisierte freie Assoziation, so als ob man eine Abfolge von Träumen anstelle einer linearen Erzählung lesen würde. Die Ausgewanderten beginnen: Ende September 1970, kurz vor Antritt meiner Stellung in Norwich, fuhr ich mit Clara auf Wohnungssuche nach hinaus. Aber Clara wird bald zurückbleiben, und der Ich-Erzähler-Ich wird nie mehr als ein schattenhaftes Pronomen sein, wie der Erzähler in Die Ringe des Saturn, der seine Geschichte eröffnet: Im August 1992, als die Hundstage ihrem Ende zugingen, machte ich mich auf eine Fußreise durch die ostenglische Grafschaft Suffolk, in der Hoffnung der nach dem Abschluß einer gößeren Arbeit in mir sich ausbreitenden Leere entkommen zu können.

...

Er hatte sich als weniger abweisend erwiesen, als ich erwartet hatte. Als ich an jenem Morgen mit dem Zug aus London in Norwich ankam, wartete Max bereits am Tor. Ich erkannte ihn von dem Foto auf der Rückseite von Die Ausgewanderten.

Anfangs war er schüchtern, als wir in seinem klapprigen Peugeot durch die Straßen von Norwich fuhren, aber bald wurde er gesprächig, zeigte auf die normannische Kathedrale aus dem elften Jahrhundert, die die Stadt überragt, und erzählte von seinen Geschäften mit Verlegern, Agenten und Vorschüssen - die Fachsimpelei eines Schriftstellers. "Meine Verleger sagten mir, sie hätten die Auslandsrechte nach Frankreich oder Italien verkauft - Wir haben Ihnen fünfhundert Pfund besorgt - und dann hörte ich nie wieder etwas davon", beschwerte er sich und schimpfte wie ein Journalist bei Elaine's. Er wirkte auf mich auf eine ruhige, unaufdringliche Art weltgewandt, besaß ein stählernes Ego und scheute sich nicht, sich an öffentlichen Debatten über brisante Themen zu beteiligen. Als er letztes Jahr in Zürich eine Vortragsreihe über die Geschichte des Luftkriegs der Alliierten gegen das Deutsche Reich hielt, so erzählte er mir, löste dies in den deutschen Medien eine intensive Berichterstattung aus. "Ich hatte das Gefühl, dass ich einen wunden Punkt getroffen hatte", sagte er ohne erkennbares Bedauern.

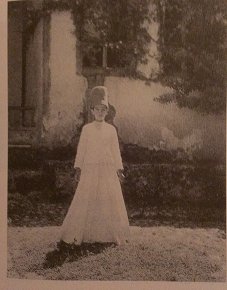

Sebald's house

Das Rectory ist ein viktorianisches Herrenhaus aus rotem Backstein mit hohen Fenstern und einem gepflegten Rasen in einer vorstädtischen Sackgasse am Rande von Norwich. Er hat es über ein halbes Dutzend Jahre hinweg in Handarbeit renoviert. Gepflegt und aufgeräumt, schien es das genaue Gegenteil seiner düsteren, grüblerisch apokalyptischen Prosa zu sein. Während wir uns im Arbeitszimmer niederließen, um uns zu unterhalten, war seine Frau Uta, eine hübsche Blondine um die fünfzig - sie hatten sich als Studenten an der Universität Freiburg kennengelernt - durch die Fenster zu sehen, wie sie mit einem Traktormäher den Rasen mähte. Morris, ihr großer schwarzer Hund, döste auf einem Kissen. Die Schlichtheit des Zimmers - Bände deutscher Literatur in den Regalen, ein blendend weißer Teppich, ein lederner Clubsessel und eine Couch, ein feuerroter Holzofen - hat mich aus irgendeinem Grund verunsichert. Der einzige exzentrische Touch war die Reihe von Hüten, die an der Wand hingen: Sie erinnerten mich an eine dieser düsteren, entvölkerten Museumsinstallationen von Joseph Beuys, bei denen die einst lebende Form durch einen alten Mantel oder ein Stück Fell dargestellt wird. Sonst hätte er auch ein bürgerlicher Ladenbesitzer in seinem Vorstadtdomizil sein können. "Ich möchte versuchen, ein normales Leben zu führen", sagte er mir - und das tut er im Grunde genommen auch. Uta, die uns Tee und Kekse bringt, ist einnehmend und freundlich; die Tochter der Sebalds, Anna, sechsundzwanzig, ist Lehrerin und wohnt in der Nähe. "Sie interessiert sich nicht sonderlich für meine Arbeit", behauptet Sebald.

...

Ich war erstaunt, als ich in Die Ringe des Saturn auf eine Beschreibung von jemandem stieß, den ich tatsächlich kannte, nämlich den Dichter und Übersetzer Michael Hamburger, der sich vor einigen Jahren aus London in ein Landhaus in Middleton zurückgezogen hat, einem Weiler etwa zwanzig Meilen von Sebalds Haus entfernt. Ich hatte ihn in den frühen siebziger Jahren kennengelernt, als ich in Oxford studierte; aber ich hatte ihn seit mehr als zwanzig Jahren nicht mehr gesehen und schlug Sebald vor, dass wir ihn besuchen sollten.

Auf dem Weg dorthin hielten wir in Southwold an und aßen im

Crown Hotel

Es war ein gemütliches Lokal mit grob gezimmerten Holztischen und kleinen Erkerfenstern, die auf die Hauptstraße des Ortes hinausgingen. An diesem winterlichen Februartag war es voller älterer Menschen in Strickjacken; Southwold ist eine beliebte Ruhestandsgemeinde für BBC-Führungskräfte, erklärte Sebald. In dem gemütlichen Speisesaal schien er sich wohl zu fühlen. Er sagte, im Crown sei er einer der Stammgäste, und er käme oft für ein oder zwei Nächte hierher, "um der Routine zu entfliehen". Es war seltsam: Sein Werk ist so unerbittlich düster, dass es ans Komische grenzt, aber Sebald selbst wirkte augenzwinkernd heiter, selbst wenn er über das Werk von Primo Levi sprach oder ein Buch über Euthanasie in Nazideutschland beschrieb, das er gerade gelesen hatte. ("Eine Anstalt in Kaufbeuren lieferte noch drei Wochen nach der Ankunft der Amerikaner Opfer ab.")

Wie die meisten Schriftsteller, die ich kenne, zeigte er ein lebhaftes Interesse an Immobilien; als wir nach dem Mittagessen durch die Stadt schlenderten, beklagte er sich, dass er eines der großen alten Häuser am Dorfplatz hätte kaufen sollen, als er zum ersten Mal in die Gegend kam; jetzt seien sie zu teuer. "In seinen Schriften kommt er als melancholischer Mann rüber", sagte Michael Hulse, "aber in Wirklichkeit ist er ein sehr lustiger Mensch. Als ich ihn auf diesen scheinbaren Widerspruch zwischen seiner düsteren Weltanschauung und seinem ausgeglichenen Gemüt ansprach, zuckte er mit den Schultern. "Man wird mit einer gewissen psychologischen Konstitution geboren", sagte er, wobei er von sich selbst in der dritten Person sprach, um jede Unterstellung von Egoismus abzuwehren, "und dann entdeckt man, dass das Leben in seiner Seltsamkeit teils entmutigend und teils erheiternd ist." Er berief sich auf Flauberts berühmten Rat, im Leben ein Bourgeois und in der Kunst ein Verrückter zu sein. "Ich möchte meinen Job behalten, damit ich nicht zu dieser Tätigkeit verdammt bin. Wäre ich meinen eigenen Instinkten überlassen, wäre ich vielleicht ein Einsiedler geworden."

Er wollte mir den

Lesesaal der Matrosen

auf der Promenade zeigen. Die Navigationsinstrumente und Barometer an den Wänden, die abgewetzten Ledersessel und Schiffsmodelle erkannte ich sofort aus

Sebalds Beschreibung in Die Ringe des Saturn. Zwei alte Männer spielten im Hinterzimmer Billard. Es war ein seltsames Gefühl, genau die Orte zu besuchen,

die in Die Ringe des Saturn so lebendig beschrieben werden - es war fast so, als wäre ich selbst in die Seiten seines Buches eingetreten. Als Schriftsteller im

Exil hatte Sebald ein so ausgeprägtes Gespür für Orte entwickelt wie kein anderer Schriftsteller, den ich kenne. Auf seinen Streifzügen durch die Gassen und Wiesen von East Anglia hatte er sich in die dortigen Überlieferungen vertieft. "Das Faszinierende an Suffolk ist für mich, dass es von der Geschichte unberührt ist, wie in gewisser Weise das ganze Land", bemerkte er. "Seit dem siebzehnten Jahrhundert hat es auf englischem Boden keinen Krieg mehr gegeben. Ich fragte ihn, ob er jemals Heimweh nach Deutschland hatte. Er antwortete: "Ja, bis ich dorthin gehe. Als ich das erste Mal hierher kam, hatte ich nicht die Absicht, in Manchester zu bleiben. Ich fahre immer noch mehrmals im Jahr dorthin, und ich habe immer wieder versucht, nach Deutschland zurückzukehren, aber am Ende komme ich immer wieder hierher zurück. In den späten 1980er Jahren arbeitete er für ein deutsches Kulturinstitut, und letztes Jahr wurde ihm eine Stelle für kreatives Schreiben an der Universität Hamburg angeboten. "Ich wollte nicht in den deutschen Kulturbetrieb hineingezogen werden. Ich fühle mich unwohl in Deutschland. Es fühlt sich an wie ein kaltes Land."

Es wurde schon dunkel, als wir die Stadt verließen und auf eine schlammige Einfahrt neben einem alten Bauernhaus fuhren. Michael, in einer abgewetzten Cordjacke,

öffnete die schwere Holztür. Er ist jetzt Mitte siebzig, aber er sah noch fast genauso aus wie damals, als ich ihn das letzte Mal sah, zerbrechlich und zaunkönighaft;

sogar sein Haar ist noch dunkel. Seine schöne Frau,  die Dichterin Anne Beresford, war ebenfalls gut gealtert. Er empfing uns in einem k

alten, feuchten Raum mit einer niedrigen, schweren Balkendecke, bleiverglasten Fenstern und einem verkohlten Steinkamin - ein Raum wie aus einem Bronte-Roman.

Überall lagen Bücher herum - in einem Schrank, in deckenhohen Regalen, aufgestapelt an der Treppe, die zum Arbeitszimmer führt. Das Haus ist "teils Stuart,

teils Tudor", sagte er. "Es stürzt um uns herum ein, aber es wird uns wahrscheinlich überleben. die Dichterin Anne Beresford, war ebenfalls gut gealtert. Er empfing uns in einem k

alten, feuchten Raum mit einer niedrigen, schweren Balkendecke, bleiverglasten Fenstern und einem verkohlten Steinkamin - ein Raum wie aus einem Bronte-Roman.

Überall lagen Bücher herum - in einem Schrank, in deckenhohen Regalen, aufgestapelt an der Treppe, die zum Arbeitszimmer führt. Das Haus ist "teils Stuart,

teils Tudor", sagte er. "Es stürzt um uns herum ein, aber es wird uns wahrscheinlich überleben.

Es war jetzt dunkel. Der Wind klapperte an den Fenstern. Plötzlich fühlte ich mich weit weg von zu Hause, so wie ich mich fühlte, als ich vor fünfundzwanzig

Jahren in England lebte, bevor es überall Telefone und Zentralheizungen gab und die Leute für ein Wochenende über den Atlantik hin und her flogen. Aber ein

paar Minuten später war es Zeit zu gehen; der Zauber war gebrochen. Zurück im Auto fuhren wir zum Bahnhof von Norwich. Sebald sprach über die Familientragödien,

die in letzter Zeit so viele seiner Freunde heimgesucht hatten. "Jahrelang kannte ich niemanden, der krank war", sagte er. "Jetzt ist es überall um mich herum."

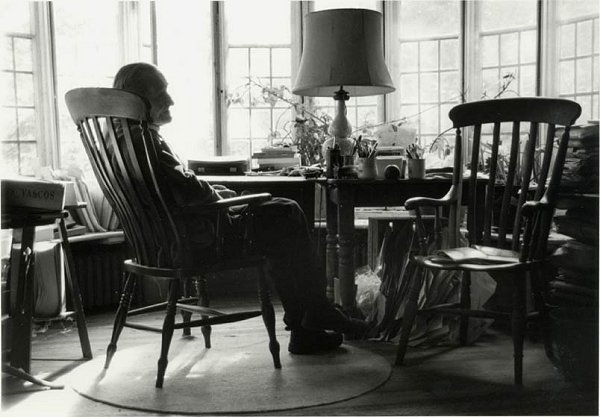

An diesem Abend, zurück in meinem Zimmer in London, schlug ich die Seiten über Michael in Die Ringe des Saturn nach. Ich hatte das Buch in der Druckfahne

gelesen und die Fotos noch nicht gesehen. Es gab zwei von Michaels Arbeitszimmer - eines zeigte seinen mit Büchern vollgestopften Schreibtisch und das alte, kleine

Bogenfenster dahinter; das andere zeigte einen Haufen Bücher, die sich neben einer Tür stapelten. Es war seltsam berührend, Bilder zu sehen, die noch vor kurzem

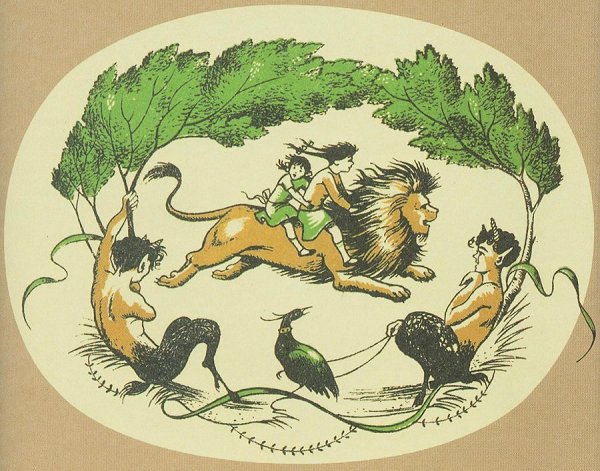

in meinem eigenen Bewusstsein verankert waren und mich von der Seite anblickten. Plötzlich dachte ich an ein Buch, das ich als Kind gelesen hatte:

C.S. Lewis' Der Löwe, die Hexe und der Kleiderschrank, in dem eine Gruppe von Kindern durch eine Schranktür klettert und sich in einer anderen

Welt wiederfindet. So war es, mit Max zusammen zu sein.

James Atlas "The Paris Review Summer" 1999, S. 278-295

|

|